A neural model of neuromodulatory (dopamine) control of arm movements

in Parkinson's disease (PD) bradykinesia was recently introduced [1,

2]. The model is multi-modular consisting of a basal ganglia module

capable of selecting the most appropriate motor command in a given

context, a cortical module for coordinating and executing the final

motor commands, and a spino-musculo-skeletal module for guiding the

arm to its final target and providing proprioceptive (feedback) input

of the current state of the muscle and arm to higher cortical and

lower spinal centers.

The neuromodulatory model is successful at offering an alternative

explanation to what other models suggest about the causes of

Parkinson's disease bradykinesia. More specifically, it focuses more

on the effects of dopamine (DA) depletion in cortex and spinal cord

and less on its effects in basal ganglia (as other models have

done).

The neuromodulatory model provides a unified theoretical framework for

PD bradykinesia and it is capable of producing a wealth of neuronal,

electromyographic and behavioral movement empirical findings such

as:

-

Increased cellular reaction time

- Prolonged behavior reaction time

- Increased duration of neuronal discharge in area 4 preceding and

following onset of movement

- Reduction of firing intensity and firing rate of cells in primary

motor cortex

- Abnormal oscillatory GPi response

- Disinhibition of reciprocally tuned cells

- Increases in baseline activity

- Repetitive bursts of muscle activation

- Prolongation of premotor and electromechanical delay times

- Reduction in the size and rate of development of the first agonist

burst of EMG activity

- Asymmetric increase in the time-to-peak and deceleration time

- Decrease in the peak value of the velocity trace

- Increase in movement duration

- Substantial reduction in the size and rate of development of

muscle production

- Movement variability

Recently the model of PD bradykinesia [1, 2] was extended in two ways:

(1) Incorporated the spindle feedback not only in the spinal cord as

in [1, 2], but also in cortex and examined its effects on the

activities of specific types of cells found in primary motor cortex

both in normal and in DA depleted cases, and (2) Examined the effects

of DA depletion not only in alpha motoneuronal (MN) and Renshaw

activities as in [1, 2], but also in the activities of type Ia and Ib

inhibitory interneurons (IN) and primary spindles, in order to

inverstigate whether abnormal reciprocal inhibition of spinal IaINs

plays a significant role in PD rigidity.

The new model [3] predicted that the reduced reciprocal disynaptic Ia

inhibition in the DA depleted case doesn't lead to the co-contraction

of antagonist motor units. Furthermore, the model predicted that

although the co-contraction of antagonist muscles might be a mechanism

for PD rigidity, the co-contraction isn't due to abnormal reciprocal

inhibition at the spinal level. The causes of MN co-contraction ought

to be searched more centrally, potentially in the microcircuit of the

motor cortex and/or the basal ganglia.

References:

[1] V. Cutsuridis, S. Perantonis (2006) A Neural Model of Parkinson's

Disease Bradykinesia. Neural Networks 19(4): 354-374

[2] V. Cutsuridis (2006) Neural Model of Dopaminergic Control of Arm

Movements in Parkinson's Disease Bradykinesia. In: Artificial Neural

Networks - ICANN 2006, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, LNCS 4131

(Springer-Verlag, Berlin) 583-591

[3] V. Cutsuridis (2007) Does Abnormal Spinal Reciprocal Inhibition

Lead to Co-contraction of Antagonist Motor Units? A Modeling

Study. International Journal of Neural Systems, in press

Model usage:

Extract the folders in this archive, start matlab, add the

Cutsuridis_PDmodel folder to the path,and run main.m

This will generate a few figures associated with the

publications:

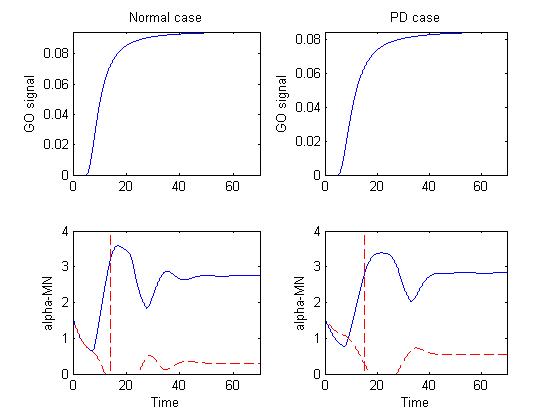

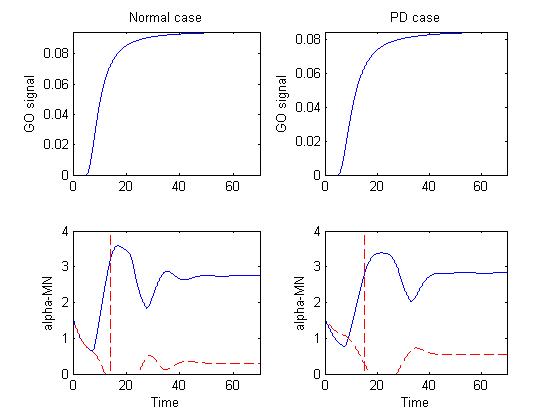

Figure 1 depicts the basal ganglia-thalamus output (GO signal) that

drives the motor cortical cells in the model and alpha-MN activity in

both normal and PD cases.

Figure 1 depicts the basal ganglia-thalamus output (GO signal) that

drives the motor cortical cells in the model and alpha-MN activity in

both normal and PD cases.

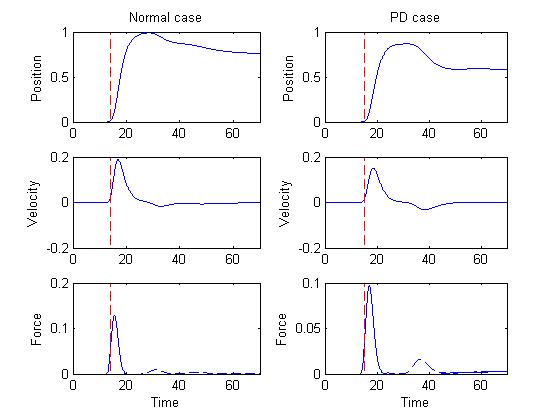

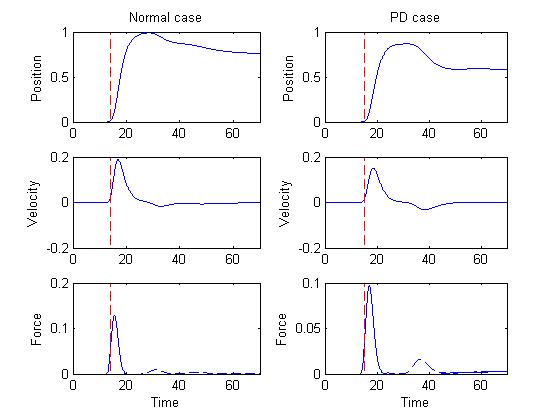

Figure 2 depicts the position, velocity and force curves in both

normal and PD cases.

Figure 2 depicts the position, velocity and force curves in both

normal and PD cases.

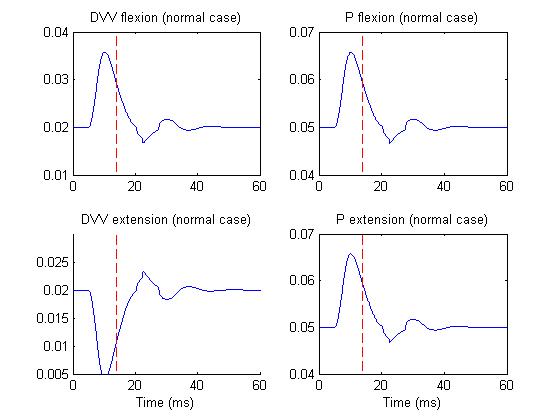

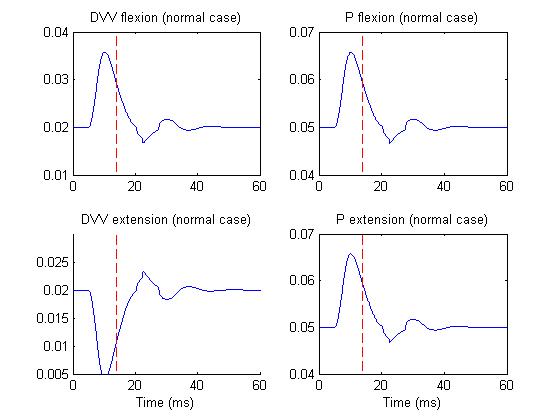

Figure 3 depicts the DVV and P activities of M1 cells in normal case,

whereas

Figure 3 depicts the DVV and P activities of M1 cells in normal case,

whereas

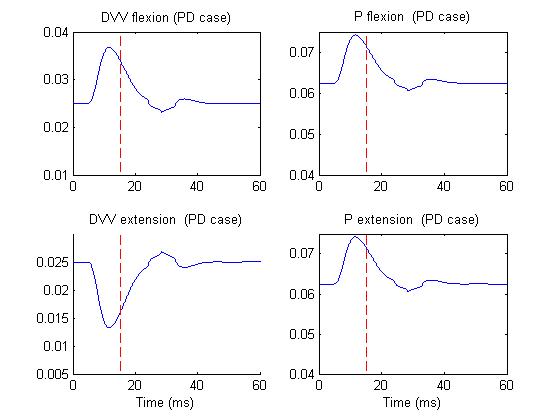

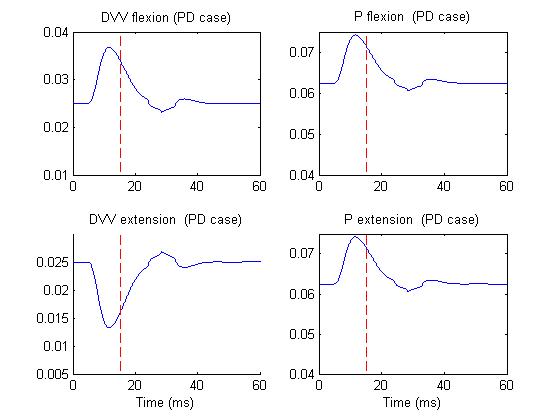

Figure 4 depicts the same activities but in PD case.

Figure 4 depicts the same activities but in PD case.

This version of the files is June 28, 2007 supplied by Vassilis Cutsuridis.

Figure 1 depicts the basal ganglia-thalamus output (GO signal) that

drives the motor cortical cells in the model and alpha-MN activity in

both normal and PD cases.

Figure 1 depicts the basal ganglia-thalamus output (GO signal) that

drives the motor cortical cells in the model and alpha-MN activity in

both normal and PD cases.

Figure 2 depicts the position, velocity and force curves in both

normal and PD cases.

Figure 2 depicts the position, velocity and force curves in both

normal and PD cases.

Figure 3 depicts the DVV and P activities of M1 cells in normal case,

whereas

Figure 3 depicts the DVV and P activities of M1 cells in normal case,

whereas

Figure 4 depicts the same activities but in PD case.

Figure 4 depicts the same activities but in PD case.